Every software professional that has been part of more than one project knows for sure: no two projects are the same. Different circumstances make most software projects unique in several aspects. And with different situations come different approaches to handle project life effectively: there are multiple ways to "do" a project. Different circumstances require different approaches.

Although a project is to a large part defined by the required end results and technology used, the main determining factor of what makes a project different from another is people. The entire process of software project management is strongly stakeholder-driven. It is their wishes, fears, dreams their stakes that determine the course of the project. You have to handle a project to really grasp the impact of people on your endeavour. You have to "live" a project to know the force of political games and power trips. You have to lead a team to deliver a project under time pressures to appreciate the constructive power of motivated people or the destructive power of demotivated team members.

In a project, it is the people that are the main cause of problems. Time schedules, financial projections, and software goals may be abstractions, but it is the flesh-and-blood people whose work determines your project's status. It's the programmer that misses a deadline and holds up everyone else, it's the financial manager that goes berserk if you can't produce some good budgetary indications, and it's the key user that doesn't give a darn but didn't tell you about his dismal lack of motivation; these are the folks who can cause serious trouble.

Stakeholders and the Software Project Manager's Problem

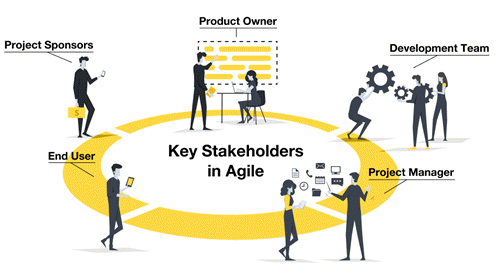

So, as a software project manager, you should really focus on the stakeholders. You should be guided by their fears and their wishes. A stakeholder can be a project team member, an employee of the user organization, or a senior manager. It can be virtually anyone, as long as that person has something to do with the project.

Here is the central problem the software manager is faced with, appropriately named "the software project manager's problem,"as explained by Barry W. Boehm and Rony Ross [1]. They believe that everyone affected by the project, directly or indirectly, has something to say, again directly or indirectly, and will do so. All of them want to get the best from this project for themselves personally or for their organization. It is the job of the software project manager to see that everyone gets what he or she wants, in one way or another. He has to "make everyone a winner."

Of course, this is easier said than done. You have to act like a psychoanalyst and get in touch with everyone's deeper feelings. Most technical project leaders would be running for the door at this moment. To make it less fuzzy, we can attach some project management lingo to it:

"The project manager can use stakeholder analysis to determine the stakes and expectations of the stakeholders, and adopt the project organization and feedback mechanisms according to the desired outcomes."

Expectations, Interests and Requirements

Stakeholder analysis is a technique to identify and analyze the stakeholders surrounding a project. It provides information on stakeholders and their relationships, interests, and expectations. A proper analysis of the stakeholders will help you to construct a project approach suited to the situation and will allow you to negotiate better with the stakeholders.

What people (and therefore your project stakeholders) really, really, really want is what can be termed their interests or, as I sometimes call them, their stakes (hence the name "stakeholder"). With fears there is a stake to lose, and with wishes there is something to gain.

In this context, I consider interests as the aspects that drive people. Before you start drawing your "interest evaluation diagram" or some other tool or technique, be aware that in general these interests are hardly ever communicated. It is pure mind stuff, all inside the head of the owner. A four-year-old boy may share his true interests with you, but the fifty-year-old greying accountant will tell you nothing.

If no one will tell you anything, what is the point? People will tell you something if you ask them. They will tell you they want an ice cream cone, a new hyper speed Internet uplink, or a new financial software package. In essence, they tell you what they expect. It is a statement created by themselves about a desired situation: their expectations.

If I emphasize that expectations are a one-sided communication, then there must be something else as well; enter requirements. Requirements are a set of statements negotiated among a group of people. They can be the original expectations, if all agree on the statement itself, but more often than not, requirements consist of some consensus of conflicting expectations.

It sounds simple, but getting the expectations is one thing and discovering their corresponding stakes is another. Why bother anyway? What is it worth? A lot. You can't effectively change the stakes, but you can alter the set of requirements as long as the new requirements continue to support the stakes. In this way, there is room to negotiate a set of requirements for the project that poses no conflict, matches the stakes, and thus makes everyone a winner!

Consider this example: a stakeholder formulates an expectation for the software project; for example, senior management states that "The project should be finished before the end of August." The project manager then has to deal with this time frame. When this deadline is no problem, he can rest assured; however, it is a software project, so the deadline typically will be a problem. The way to handle it is to get some information on the stakes that prompted this requirement to be formulated in the first place.

Perhaps it is the old "I don't want to lose face when my projects get delayed" concern. That being the case, the project manager can offer alternatives that don't violate the stake, like keeping the deadline but postponing a subsystem. Chances are good that alternative requirements that keep supporting the stakes will be accepted maybe not easily, but project managers should do something to earn their money.

So, it seems to be valuable to dig deeper into the souls of your stakeholders. It sounds all very misty and cloudy, but keep remembering why you must do it:

- Expectations are assessable and can be influenced. However, you should stay true to the interests of people; they will determine the amount of leverage you have to change the expectations without setting a stakeholder on the warpath.

- Requirements have to stay in line with what people are expecting. If stakeholders find out the requirements don't fit their expectations, you have a major problem.

- Knowledge about the stakeholders and their expectations and interests helps you shape the project organization (structure, authority, and responsibility).

- It is a very good risk analysis strategy to see where the potential problems will be.

Stakeholder Analysis

The actual steps for a stakeholder analysis are:

- Stakeholder identification

- Stakeholder expectations and interests

- Stakeholder influence and role in the project

Stakeholder Identification

This first step is concerned with the question "Who are the stakeholders?" For this, you basically draw maps of people or groups and their relationships. You start with two names on a whiteboard and before you know it, you are drawing on the walls.

Stakeholder Expectations and Interests

The more difficult step is this one; here we get the socio-psycho stuff. For expectations it is fairly straightforward: just ask. You can ask in person or via mail or email. Create some variations on the question, so that it is not too obvious what you are trying to find out.

Stakeholder interests are another thing. Trying to elicit their interests is always guesswork, deducting them from other information. For this, there are two types of approaches: (1) using a checklist to assist your thinking about the stakeholder and (2) plotting people in small models that help determine the way to approach them.

For the first type, consider a list with questions like: "Is he satisfied with his current job?", "Is he covering up his own incompetence?" and "Does he want a bigger office?" Thinking about these questions help you build an image of the person's interests. Consider the list at the end of this article as good starting point.

Using small models, the second type, can be easier than it sounds. For this, you have to plot a stakeholder in a dimension, and by doing that, you get an idea of how to approach the stakeholder. Dimensions can include: "How much in favour of the project", "Process or Content-oriented" and "Group or Individual-oriented."

Stakeholder Influence and Role in the Project

The insights about the stakeholders will assist us also to construct the project organization:

- Do we have to include the stakeholders in the organization?

- If so, is it wise to grant stakeholders great influence or should we give them positions where they can do no harm?

- How can we construct stakeholders's job descriptions in such a way that they are as motivated as possible?